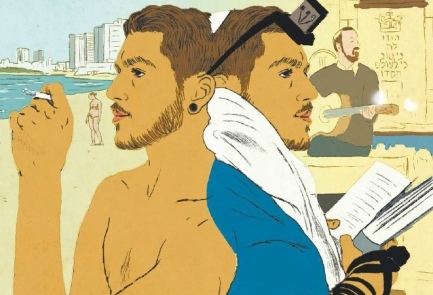

Photo credit: Ruth Gvili Tel Aviv, the city that never sleeps and is so strongly identified with its nightlife and party scene, has been seeing a “renewed interest” in Jewish tradition — not out of religious coercion, but out of respect for and understanding of Jewish tradition.

The Tel Aviv version of Judaism:

Friday, June 13, 2014, three and a half months ago, was a significant day. That morning, rumors about the three kidnapped boys from Gush Etzion began to circulate. Tel Aviv was divided in two: Dozens of people gathered for a celebration of sexual liberation at the Gay Pride march near Charles Clore Park, while the final preparations were underway at Hangar 11 in the Tel Aviv Port for the largest Sabbath meal on earth, which would make the Guinness Book of World Records.

Tel Aviv, the city that never sleeps and is so strongly identified with its nightlife and party scene, has been expressing an interest in Judaism for some time. This is no mass movement toward becoming religiously observant, nor is the city’s secular population shifting toward religious belief. The people who live in the midst of it describe it as “renewed interest” in Jewish tradition — not out of religious coercion or a need to delve into the pages of the Talmud, but out of respect for and understanding of Jewish tradition. It is also fueled by a thriving social scene, where groups of people meet for prayer services, classes on various topics and meals that might feature the classic Ashkenazi dish cholent or the classic Mizrachi dish jachnun.

* * *

A major part of this interesting scene is Tel Aviv’s synagogues, which are filling up with secular people once again. For example, the influx of newly interested young people has revived three large synagogues in a 300-meter radius of each other on Ben Yehuda Street that were on the verge of closing their doors.

One of these synagogues is the North Central Synagogue. “Until four years ago, this synagogue hardly got 10 people in the evening and 10 elderly people on Saturday morning. A group of young people started coming here recently. They’ve brought more people with them, held events, meals and kiddushes after services, and now 250 people come here every Saturday morning,” says Rabbi Yitzhak Bar-Ze’ev. “All kinds of people go there — religious and secular. One person even comes straight from the beach.”

Bar-Ze’ev, 26, married and the father of two, is just starting out as a rabbi. He studied at an ultra-Orthodox yeshiva high school and then at the prestigious Hebron Yeshiva. Although he serves as rabbi of Tel Aviv’s largest synagogue, he spends most of his time at the North Central Synagogue.

Bar-Ze’ev says that because of the recent increase in the number of young people in Tel Aviv and the desire to set a good example, he decided to enlist in the army. “All the young people around me did army service and it’s not dignified that their rabbi did not. Along with my rabbinical duties in Tel Aviv, I serve in the Air Force’s rabbinate every day from nine in the morning to four in the afternoon.”

To the question of how he explains the renewed interest in Judaism, he replies, “Traditional people are searching for a taste of the Sabbath atmosphere — secular people with warm hearts who want the spiritual atmosphere, and religious people alike. Another reason is the fact that the young people adapted the synagogue for people in their own age group, and they hold kiddushes there and the number of participants just goes up. There’s a very special feeling. Young men and women meet one another — all of that creates the experience. It’s very similar to what happens abroad. Everyone belongs to the community in the end.”

A cantorial concert on the Sabbath

Another synagogue that closed for lack of worshippers — and reopened — is Tel Aviv’s Great Synagogue, a magnificent old building that seats 1,500 people. “The worshippers left it slowly, over many years,” says Bar-Ze’ev. “That also happened to the rest of the synagogues on Allenby Street, which became mostly a commercial area. It reached a point where it had almost no worshippers; only 25 people in such a big place.”

Four months ago the chairman of the board, who was more than 80 years old, was replaced, and the cantor of the Israel Police was appointed. The cantor appointed Bar-Ze’ev as the synagogue’s rabbi in the hope that a young rabbi would attract young people, and so it was. “A revolution is under way here, too, like in the other synagogues. On weekdays the synagogue is full because of all the people who work in the area, and young men and women come here on Saturdays. We have had some nice events, such as a mass prayer service and meal on Shabbat for 350 young people. After years of counting for nothing, the Great Synagogue is suddenly making a local splash.”

Bar-Ze’ev describes that Shabbat meal. “We sang ‘Shalom Aleichem’ and then we had a cantorial concert. The biggest accomplishment is that since then, on Friday evenings there are several dozen young people after 15 years during which the synagogue was closed because of a lack of worshippers. We should remember that this is the city’s Great Synagogue, which has existed for 85 years — Ben-Gurion and Bialik prayed here, and Rabbi Yisrael Meir Lau was formally invested here as the chief rabbi of Tel Aviv.”

The Ichud Shivat Zion Synagogue, also on Ben Yehuda Street, is one of the largest synagogues in Tel Aviv, particularly after new immigrants from Australia, Great Britain and the United States started attending. Another synagogue that attracts young people is Beit El on Frishman Street, where Rabbi Ariel Konstantyn of the Tzohar rabbinic organization presides. “There are enough young people to go around. The graph is in an constant increase,” Bar-Ze’ev says.

One of the young people taking part in the reawakening of interest in Judaism is Natan Bashevkin, a participant in the reality television show “Survivor” who attends the North Central Synagogue. “At first I went to the nearby synagogue until an older man told me that they needed help bringing people in for the minyan [basic quorum of 10]. He told me that people might attend because I was well-known. We were seven people at first, and every time they would send me outside to ‘hunt’ for people to make the minyan.”

Bashevkin does not define himself as religious or secular. “I maintain tradition — that’s the definition I came up with for myself,” he says. “I maintain the tradition of the Jewish people and try to pass the values of Judaism on. I do not observe the Sabbath but I put on tefillin, make kiddush on the Sabbath and keep meat and dairy separate.” He adds, “The synagogue is open to anyone who wants to come. Nobody bothers anyone, and the prayer services aren’t abridged or drawn out. Everything is done with love and free will.”

Bashevkin also attributes the Jewish awakening in Tel Aviv to Operation Protective Edge. “There’s more awareness of Jewishness,” he says. “After the military operation, people realize that it’s impossible to live without a drop of faith or a path. Those who have no path and no goal get lost. Recently, it has seemed to me that people are starting to become stronger in their faith. It is not about keeping the Sabbath or becoming really religious, but about introducing the Torah to someone. People are realizing that last summer was a kind of miracle: Dozens of rockets fell and almost no one was killed. That cannot be denied.”

Bar-Ze’ev is also not in a hurry to turn Tel Aviv into a city of religious people. “Because of the openness that exists in Tel Aviv and because everybody is pleased and there are people of all kinds, it is easier for secular young people to go with what they feel because they do not feel like they are different. After all, this is not coming out of coercion, but because they are free. They come because of the atmosphere of freedom. Many people want to taste the tradition that existed in their parents’ homes.”

Social networks have found their way into the synagogue, as well. “Every synagogue has its own Facebook page,” Bar-Ze’ev says. “The North Central Synagogue’s page has more than 2,000 members, the Great Synagogue’s has more than 700 after just four months of operation, and Frishman has 2,000 also.”

These Facebook pages show what “Tel Aviv-style Judaism” looks like. For example, the North Central Synagogue invited worshippers to the installation of a new Torah scroll and a street party. One can find posts by members who are subletting apartments in the city alongside posts giving the starting and ending times for Shabbat and invitations to kiddush get-togethers.

Stamping out the stigmas

Liat Gorsetman, 36, of Tel Aviv, a “secular person with a connection to tradition,” as she describes herself, says that she, too, has experienced the religious blossoming in the city. “I have known Tel Aviv for many years, and it was not what it is today in terms of its relationship to Judaism. Someone in the religious establishment realized that in order to avoid going extinct, they needed to open their doors to non-observant people who were on the seam — neither religious nor secular. There are several organizations in Tel Aviv that do it right.”

One such group, she says, is Aish Tel Aviv. “It is an organization that asks secular people to come and get to know Judaism in a non-coercive manner, not like Jewish revival groups. They have coordinators and people meet there to celebrate festivals, have Friday night meals and listen to talks that are easy to connect with, such as the Jewish perspective on how people should treat one another, practical things that any person can connect to. There are lots of people like me; if it were not for this, many of us would have no connection to Jewish tradition.”

She says that the media contains anti-religious incitement, and as a result of that, secular young people flinch from Judaism. “It is hard to tell exactly what happened, but spirituality and Judaism became ‘cool.’ Many people are interested in spiritual things. We live in a Jewish state; one cannot pass religion by and ignore it. It’s a part of us.”

Rabbi Shlomo Chayen of Aish Tel Aviv says, “We no longer call it kiruv [the term usually used for teaching non-observant Jews about Judaism]. To call it that is to say that I have all the answers, so come and be like me. I don’t want them to be like me. The Torah and the Creator don’t belong to one person. No one owns them. It is true that there are rabbis and people who make decisions of religious law. I do not deny that. But we are talking about Judaism as Jewish wisdom — wisdom that has accompanied us for three thousand or four thousand years, and each person connects to it and takes it to his own place. It is wisdom for life. Each person can find authentic things in it that are right for him — core values that preserved this family known as the Jewish people all these years.”

Chayen says that Judaism places a great deal of importance on debate. “We have arguments that are fun. There’s a dialogue that does not come from a place of who is better. I do not like the definitions of religious, secular, traditional or haredi. We need to take them out of the lexicon. Even when there are controversial subjects such as whether to have public transportation on Shabbat or keep grocery stores open then, they need to be discussed. If we say that there is no status quo and therefore the rabbinate has nothing to say in the matter, everything is open on Shabbat and we have civil marriage, then what defines us as Jews? I don’t say what does that. Many times we remain with no answer, and that is fine. The idea is just to make us think about it.”

Lau, the chief rabbi of Tel Aviv, is familiar with the renewed interest in Judaism and Jewish tradition in his city, and has an explanation. “The wave of immigration from France can explain it,” he says. “Five communities of French immigrants were established here thanks to that wave of immigration, made up of Jews who may not define themselves as religious or haredi but are so traditional that they cannot allow themselves to go a week without walking into a synagogue. There is even a prayer group of Italian immigrants, and Ichud Shivat Zion is true to its name: More than 200 young people from all over the world meet there every Shabbat for a large prayer service and social activities. That did not exist before.”

Lau says that Judaism and Jewish tradition played a major role in Tel Aviv at first, but their influence later declined. “The city of Bnei Brak was built on the ruin of Tel Aviv,” he said. “Masses of Hassidim who lived in the Florentin neighborhood of south Tel Aviv moved to Bnei Brak. Later on, the national-religious community migrated to Raanana, Petach Tikva, Kfar Saba and Givat Shmuel.” Those who are still responsible for Judaism’s resurgence in Tel Aviv are the small groups of strongly observant people. “There are a few such groups — groups of religious people who came to live in the city, from Ramat Aviv Gimmel to Jaffa. They established yeshivas and schools for their population.”

Lau admits that besides them, he does not see any mass movement of young secular people toward their Jewish roots. “There are a few secular people in each synagogue in the city who join the prayer services and attend, but they are a very few. But the phenomenon is positive and exciting.”

Still, Tel Aviv’s synagogues are more numerous than can be described. “When I ask people how many synagogues they think are in Tel Aviv, they answer: five or 10. The most they say is 30. People don’t believe it when I tell them that there are 547 active synagogues in Tel Aviv.”

The Tel Aviv version of Judaism