HOWARD EPSTEIN’S LETTER FROM ISRAEL OUR SPIES IN THEIR MIDST

Imagine a darkened stage, suddenly illuminated with three pools of light. Now the audience sees the same number of actors, two men, and a woman. Thus opens Michael Frayn’s 1988 play ‘Copenhagen’, which explores the 1941 visit of Werner Heisenberg to the eponymous Danish city, to see his former mentor and close personal friend, Niels Bohr (and incidentally Mrs. Bohr).

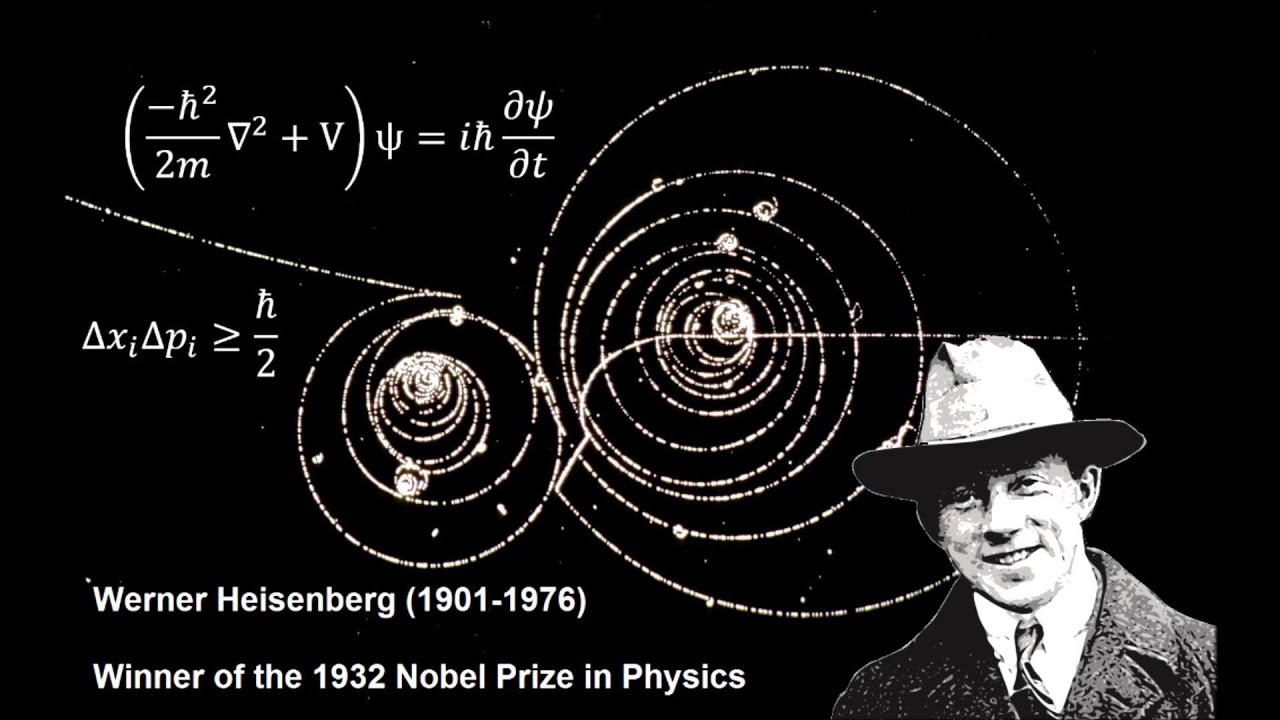

Frayn’s brilliance was to link Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle to the purpose of his meeting with Bohr, under the noses of the Gestapo in Nazi-occupied Denmark. What on earth did they discuss? It is uncertain to this day. (They could not even agree upon it when they met after WWII.)

The backstory is that these were two of the foremost physicists on the planet, and in 1941 Heisenberg was one of the leading lights in Hitler’s programme to build the atomic bomb. Bohr’s mother’s Jewishness was enough for the Danish underground to smuggle him in 1943 to nearby Sweden, en route to London. Finally, he joined the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos, where, debriefed, he told his handlers that he understood that Heisenberg had wanted to impart the warning that the German project was going well, and the Americans had better get their skates on.

After the end of WWII, when the British Army broke into Heisenberg’s laboratory at Haigerloch, on the edge of the Black Forest, they discovered a different truth – a rudimentary nuclear reactor lay in a pit in the ground, going nowhere and certainly incapable of a chain reaction.

It was another physicist who conceived of the nuclear chain reaction. Jewish Hungarian, Leo Szilard’s lightbulb moment occurred close to the British Museum in London. After nine month’s hard work he patented it and handed his truly intellectual property over to the Royal Navy, to be subjected to the Official Secrets Act. After that, Szilard went to America, where (to cut a long story short) he got the attention of President Roosevelt sufficiently to have him initiate the Manhattan Project in time to bring the war against Japan to an abrupt end over Hiroshima in August 1945, thereby saving probably some six million lives (although that’s another story).

Now, the point of departure between Szilard and Heisenberg was that Szilard worked out how to control a nuclear chain reaction and Heisenberg did not. Both knew that graphite would be the moderator to do the trick, but Szilard alone appreciated that the graphite had to be pure and boron-free.

Given the genius of Heisenberg, and the simplicity of the solution, historians have long questioned whether Heisenberg, who was never trusted by the Nazis, secretly wanted the German effort to fail – and that was what he had wanted to tell Bohr.

Those of you who are still with me and have not given up at the apparent irrelevance of this tale to Israel may already have guessed at the connection.

While the Americans are witlessly appeasing the Iranians in Vienna, and having Persian rings run around them, the Jerusalem Post last Friday carried two stories that possibly echo that of Heisenberg. Reportedly, last April as many as ten Iranian nuclear scientists helped destroy large numbers of centrifuges at the Natanz nuclear facility. They may or may not have known that it was Mossad who recruited them but the outcome of the work of the sleeper spies within the Iranian nuclear project was as destructive as several that have preceded it, and very much to Jerusalem’s satisfaction.

And the other relevant story? At an award ceremony for twelve Mossad agents who received certificates of excellence, David Barnea, their boss, pledged, “Iran will never have nuclear weapons – not in the coming years, not ever. This is my personal commitment: This is the Mossad’s commitment.”

There must be a belief beyond Jerusalem, too, that Israel that it is here to stay. Currency traders certainly are not marking the shekel down out of fear for its longevity. In a market invariably driven by news and sentiment, it is, after years at the top, still the world’s strongest currency.

And not many think Tel Aviv has a limited future either. Last week’s news told us that it has overtaken Paris as the world’s most expensive city.

Coincidentally, less than 200 kilometres to the east is the world’s cheapest city. Fancy living there? It’s heavily influenced by Iran – but cheap is cheap so, if you are attracted to saving money, go for it. Just key into Waze D A M A S C U S

© December 2021 – Howard Epstein