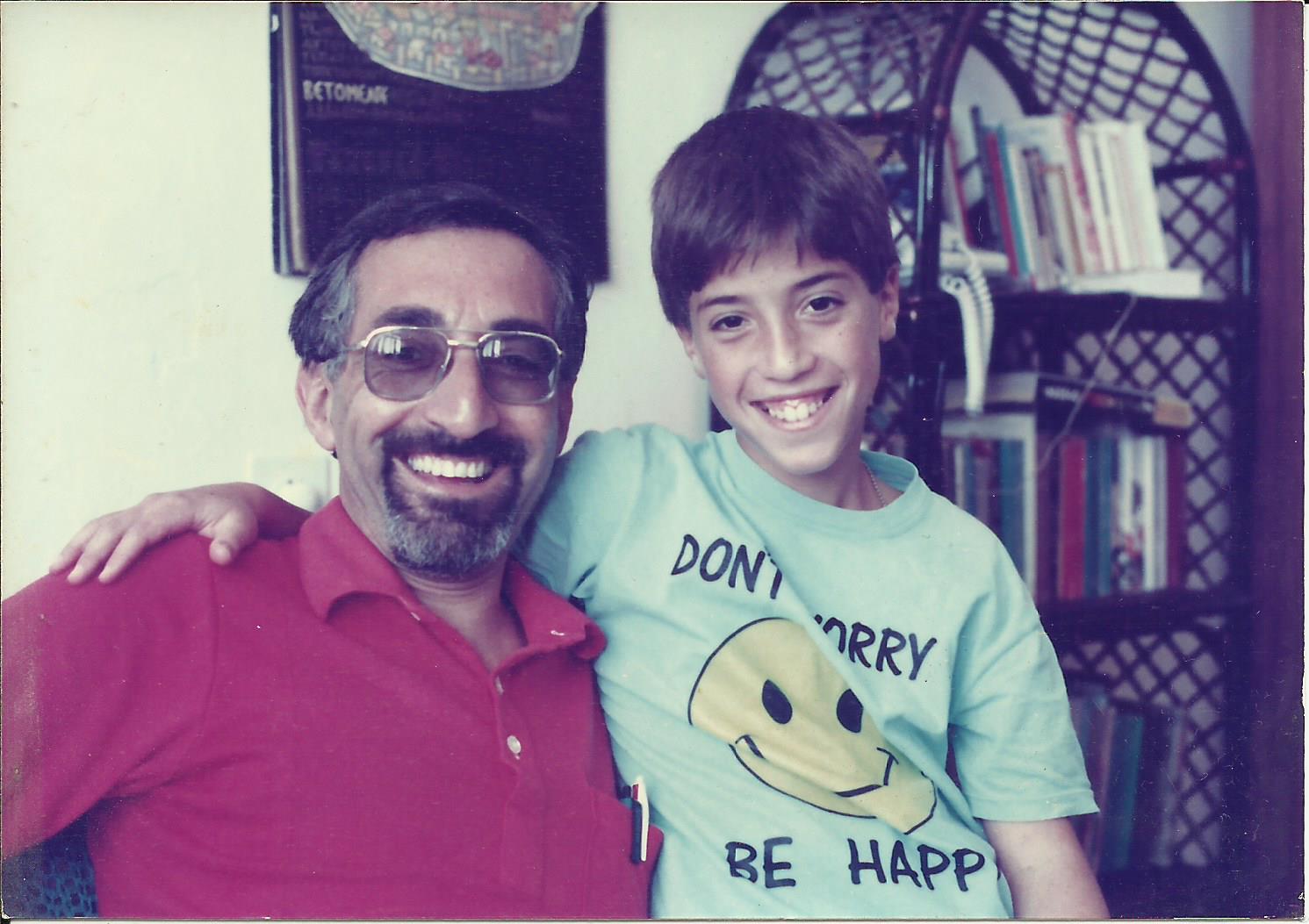

Nadav Aged Eleven

Our dear friend and contributor David Lawrence-Young just recently lost a son to an accident and wrote two blogs about him and the process of mourning in Judaism.

We share his personal reflections about his son Nadav z”l.

My favourite picture of Nadav

This blog is dedicated to my son – NADAV AVRAHAM YOUNG whose untimely demise occurred on May 19th.

Although I wrote in my last blog a few days ago that this one would be about the Elizabethan actor, Edward Alleyn, fate – “the stars above us [that] govern our conditions”(Lear IV,3) – hath intervened and declared otherwise.

Two nights ago, my son, Nadav, saw that he had forgotten or misplaced the key of his flat in Tel-Aviv late that night. He had returned from where he’d been working at the theatre and decided to try and get into his flat through the outside balcony. Unfortunately he slipped and fell into the garden below. If there’s any chink of comfort in this story, it’s that he didn’t suffer as he died instantly. He was 37 years old, unmarried and a popular and talented musician.

As I said at his funeral, it is against the natural order of things for a father to bury his son, but that is what happened. What is natural for me, that is, was to turn to Shakespeare to see how I could express myself with regard to this tragic situation.

Death appears in many guises in WS’s plays. According to several sites on Google, the majority of deaths in the Bard’s works are the results of stabbings (e.g. Duncan in Macbeth, Claudius in Hamlet and also in Julius Caesar,) death by sword and/or combat as in Macbeth, Richard II & III. Suicide also occurs as in Romeo and Juliet and Ophelia in Hamlet, as well as death by smothering as that of ‘the true and loving, gentle’ Desdemona in Othello. Another grim death is that of Cordelia, ‘the precious maid.’ She dies by being hanged by her enemies at the end of King Lear, a play in which her royal father also dies, but he dies of a broken-heart.

Shakespeare even wrote about a fake death: the ‘death’ when the spurned Hero in Much Ado pretends to die in order to regain Claudio’s love.

Nadav and his sister, Vered

However, these deaths for Shakespeare were vicarious and didn’t affect him personally. Apart from the death of his younger eight year old sister, Anne, the one death we know that did influence him was that of his son, Hamnet. This young lad died aged eleven in August 1596. It has since been claimed by many that the following lines said by Constance, the mother of the murdered young Arthur in King John probably reflect Shakespeare’s own grief over the death of his young son. These lines were written in 1596-97.

Grief fills the room up of my absent child,

Lies in his bed, walks up and down with me,

Puts on his pretty looks, repeats his words,

Remembers me of all his gracious parts,

Stuffs out his vacant garments with his form:

Then I have reason to be fond of grief.

I am now grieving my own son’s death. What makes this even harder is that Nadav’s death was completely pointless. It did not achieve anything. No-one gained from it but many people including his many friends and family certainly lost by it. As Shakespeare said at the end of Macbeth in that fantastic speech beginning, Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow about life and death, life

‘is a tale,

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.’

Nadav’s life was not pointless. His death was.

David, May 22nd. 2016

My last memorial blog for Nadav: “Give sorrow words.”

This is going to be my second and last blog in memory of my son, NADAV AVRAHAM YOUNG, (3 July 1978 – 19 May 2016) who died in a domestic accident last week.

My favourite picture of Nadav

This blog will also serve as a genuine heartfelt ‘thank you’ to all the people who took the time and trouble to personally console me and my family during this terrible period. That means it is addressed to the tens of people who came to our house and also to all of the others who sent us email messages of condolence. Please regard this blog as a personal and individual way of saying ‘thank you’ for your support.

These past few days when we have been sitting shiva – the traditional seven days of mourning in the Jewish religion – have given me time to think about two important aspects of mourning. The first one of course was the mourning for my son, Nadav, and the second one was to think about the nature of mourning and how we cope with death.

Apart from sitting shiva for my parents and my older sister, Frances, I have not had much experience of sitting shiva.

However, it was THIS shiva which made me think about the essence of this tradition i.e. how we Jews mourn and how other religions cope with this situation. Buddhists and Hindus believe in different variations of embalming and cremating while Quakers have very few strict rules about memorial rites. They believe that the dear departed should be the subject of a thoughtful “meeting for worship” as opposed to the Irish wake style of memorial. Moslems, like Jews, believe that apart from the saying of specific prayers and the carrying out of certain rituals, the deceased should be buried as quickly as possible after they have died if the circumstances allow.

This Jewish tradition of the shiva is based on the Old Testament, (Genesis 50: 1-14) when Joseph buried his father, Jacob, before sitting for seven days in mourning. As a continuation of this ancient tradition, during the shiva today the bereaved family sit on low chairs, do not go to work and the men refrain from shaving.

All of this was new to me when I attended my first shiva. This was in honour of a schoolfriend’s father who had died when we were both thirteen years old. I was very loath to attend. I expected to be drawn into a very sad household where everyone would be crying and the atmosphere would be unbearably heavy. Instead, I saw that everyone was sitting around normally and talking about all sorts of things while mentioning what my friend’s father had done during his life at the same time. “Why isn’t everyone sad and crying?” I asked myself, but then didn’t give the shiva too much thought afterwards as I was busy growing up.

Today I understand the importance of this tradition. By not going to work during this seven-day period and by abandoning the normal routine of life, you are able to think more about the deceased (in my case, Nadav) while at the same time it also allows your friends and family to visit you and pay their respects. I have found that this act of ‘visiting’ and ‘hosting’ to be mutually therapeutic and supportive. It enables all of those who come to commiserate with you on your loss to do so in a quiet and calm atmosphere – an atmosphere which helps to give strength and support to everyone involved. To quote from Macbeth when Malcolm is consoling Macduff over the murder of his family “give sorrow words: the grief that does not speak whispers the o’erfraught heart.” This Shakespearean quote reflects much of the essence of the shiva.

And so I am taking this opportunity to thank all of those who contacted me, both personally or electronically, during this past week, and helped me “praise what is lost” and make “the remembrance dear.”

יחי זכרו ברוך

David

dly-books.weebly.com