We discuss what Makor Rishon might be saying through this very clever illustration, in our discussion below.

Daniel Gordis – American Jews and Israel: Shifting Sands, Again?

For years, the story has been about what American Jews were saying about Israel. Now, Israelis are talking about American Jews. And what they are saying may surprise you.

Visit Daniel Gordis web site

In October 1994, a 19-year-old Israeli soldier, Nachshon Wachsman, was kidnapped by Hamas terrorists. He was held hostage for six days during which time Israeli intelligence used every means at its disposal to learn his whereabouts, and during which time much of the rest of the Jewish world held its breath.

Eventually, having discovered the location of the hideout where the terrorists were holding Wachsman, Israel dispatched its elite commando unit, Sayeret Matkal, in a rescue attempt. Almost everything that could go wrong went wrong. The unit lost the element of surprise; the terrorists shot Wachsman in the throat and the chest, and in the firefight that ensued, the commander of the commando unit was killed as well. Several other commandos were badly wounded.

I was the dean of a rabbinical school in Los Angeles back then. We had a regularly scheduled she’ur klali (school-wide learning) scheduled for a few days later, and I decided that during that hour, which would be attended by the entire school, I would — as some small expression of the utter devastation that I felt — teach something dedicated to Nachshon Wachsman’s memory. I explained why I was teaching the text we studied, and the session proceeded uneventfully.

After the class, though, as the students spread out nonchalantly on our gigantic terrace overlooking the Santa Monica mountains and the 405 freeway, one of the rabbinical students caught up with me.

She looked at me quizzically, but not abashedly and asked, “What does what happened to him have to do with any of us?”

Today, some 27 years later, I have no recollection at all of what I taught that day. But I can still picture her standing right in front of me; I can “see” what the terrace looked like as the shock of her question registered.

Of course, I had no idea what to say. I’m pretty sure I said nothing. But I do recall having an immediate instinctive sense that she and I didn’t belong in the same institution. It never occurred to me to throw her out (and even if it had, there were no grounds), but I didn’t have to. We parted ways anyway: she decided to transfer to a different rabbinical school (and today is a practicing rabbi), and my family and I moved to Israel. (The eminent historian Gil Troy (most recently coauthor with Natan Sharansky of Never Alone), believes that American rabbinical schools should start expelling students for a lack of Zionist commitment; we posted our podcast with him, in which he explains that view, last week.)

Back then, I had no sense that this student’s question, which literally left me speechless, would soon seem entirely unsurprising. But we’ve come a long way since then. I mentioned in a previous posting the now infamous letter signed by rabbinical students during the recent conflict between Israel and Hamas. Some 90 students wrote a letter accusing Israel of “violent suppression of human rights,” in a lengthy epistle that waxed eloquent about Israel’s conduct, but made no mention of Hamas, of the fact that Israel was under attack or of Hamas’ explicit intent to destroy Israel.

In some ways, mostly unnoticed in the English-speaking and reading world, that letter may have been a turning point. Israelis began to take notice that even though the ink was still barely dry on the Abraham Accords, not a single Arab nation recalled its ambassador as Israel was pummeling Gaza. Not Egypt, not Jordan, not the UAE nor Bahrain. None of them called in the Israeli ambassadors for a “talking to,” as then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton outrageously did to Ambassador Michael Oren (see Oren’s book Ally). With Israel at war, Egypt, the UAE and Bahrain were proving far more supportive of Israel than were many American rabbinical students.

Here’s what we might not have expected when that letter came out, though. The rabbinical student letter, and a subsequent survey commissioned by the Jewish Electorate Institute, a largely Democratic group, which showed that “34 percent agreed that ‘Israel’s treatment of Palestinians is similar to racism in the United States,’ 25% agreed that “Israel is an apartheid state” and 22% agreed that ‘Israel is committing genocide against the Palestinians,’” has gotten Israelis to begin taking notice of the shift in American Jewish sentiments. And some Israelis are none too happy.

If for decades, the “news” has been that progressive American Jews are slowly abandoning Israel, the newest development now may just be that some Israelis are also beginning to wonder if there’s any basis for a continued relationship.

While others are doing precisely the opposite.

Take a look at this front page of Makor Rishon (July 16 2021), a slightly right of center paper (but with a wide editorial tent, which includes Ari Shavit and Yair Sheleg, for example), and note the red banner just above the fold (at the very bottom of the photo).

There’s a tiny picture of two people carrying a Jewish star—we’ll come back to that in a moment. But the red banner with the white lettering reads as follows:

1 in 10 American Jews believes that Israel has no right to exist; a third are convinced that Israel is an Apartheid state.

For those who follow the Israeli press (in Hebrew), this is clearly a noteworthy shift. American Jewish attitudes to Israel making the front page? When there is so much else going on?

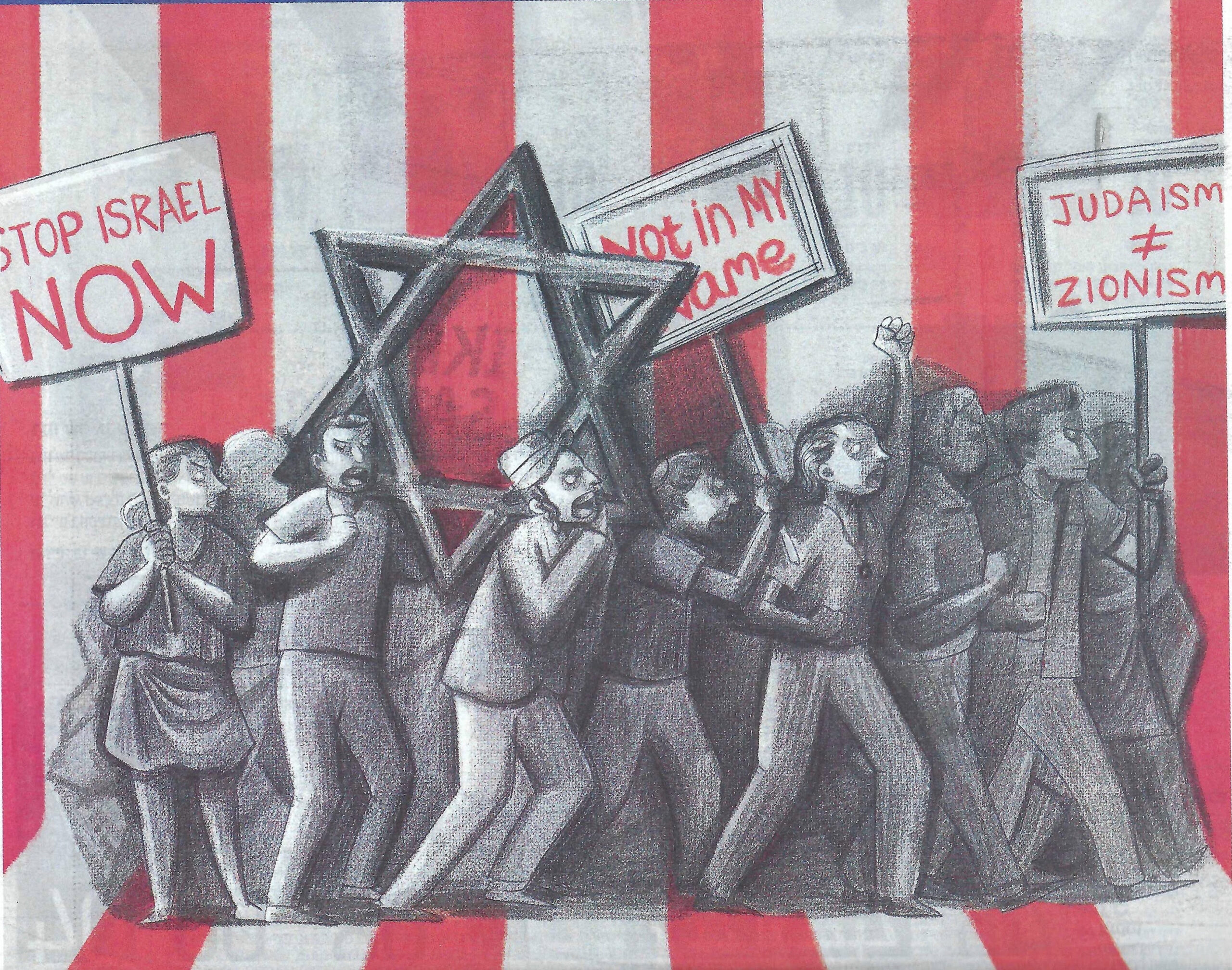

Which leads us to the little drawing of the two people carrying a Jewish star. That’s a detail from the clever and evocative drawing on the cover of the “magazine section” of Makor Rishon that week, pictured at the very top of this column.

What is the point of the drawing? Most people will recognize, of course, that the drawing is play on the famous scene on the Arch of Titus, still prominent in Rome, depicting Roman soldiers carrying off the spoils of the Temple back to Rome.

What was the artist for Makor Rishon trying to say? I suppose reasonable minds can differ, but it’s clearly something along the lines of “for thousands of years, Jews have mourned Rome’s plundering of the Temple, while today’s American Jews increasingly want nothing to do with Jerusalem or its people.” Something like that.

Again, the story is more complicated, American Jews are hardly monolithic (any more than are Israeli Jews ) and the series of articles that this cover story launched have pointed quite nicely to some of the subtleties in the American picture. Still, I’m struck by the fact that there’s a shift—the story used to be that American Jews were growing tired of Israel. Increasingly, what the news is covering is that Israeli Jews are losing patience with what seems to them an outrageous, myopic take on Israel.

And yet, the plot thickens. Not everything is headed in that direction.

There was much coverage of the ugly events that took place at the Kotel on the night of Tisha B’av a few weeks ago, when Orthodox activists disrupted egalitarian prayers at the pluralist plaza at the Kotel (see video in Gil Kariv’s tweet). (In our podcast, we spoke with Shira Ben-Sasson Furstenberg, who was present that night and described what happened.) While the disruption hadn’t been expected, it would be hard to call it shocking.

What was much more surprising, though, was some of the Orthodox reaction to the disruption. There are few Orthodox authorities more widely respected even in the “hard right” community than Rabbi Eliezer Melamed, the head of a well-known yeshiva in Har Brachah. Rabbi Melamed and his wife have thirteen children, and live in the community of Har Brachah (far over the “green line”). He is the author of a twenty-volume series on Jewish law called Peninei Halakhah, which has sold some half-a-million copies. Rabbi Melamed recently made waves by sitting on a panel with a woman reform rabbi, for which he was criticized but refused to apologize.

Perhaps even more interesting, though, in the aftermath of the Kotel incident, he came out firmly on the side of the Reform and Conservative Jews (Hebrew is here, translation is mine):

As there are many Jews who identify with the Conservative and Reform movements, and in accordance with their guiding principles, they have set up egalitarian prayer services in ways that are not in accord with the halakhah and the customs of the Jewish people, and they desire to worship near the Western Wall, it is only right that in the Ezrat Yisrael [egalitarian plaza – DG] they should be able to conduct their services with due respect. And the religious and Haredi communities who observe halakhah and Jewish customs ought not be distressed that many members of these movements come to the Kotel, but instead, ought to rejoice that more Jews feel a tie to the site of the Temple and more Jews wish to pray [there] to our Father who is in heaven; they should look favorably on all this, for even though we disagree with their changes in halakhah, we know to respect and admire all the good in them. Greater is the sanctification of God’s name [by doing so] than is the desecration of God’s name.

Rabbi Melamed also had some clear advice for the Rabbi of the Kotel:

The Rabbi of the Kotel should respect Jews of all movements. And when a group of Conservative or Reform Jews wishes to come to worship, he should greet them at Ezrat Yisrael and welcome them. And even though Ezrat Yisrael is not subject to his directives as would be a synagogue, he should still attend to the respect of this site no less. In other words, even though he cannot worship with them for halakhic reasons, he should rejoice in their coming to the Kotel and he should encourage them to come to the Kotel in groups as large as possible. And he should instruct the ushers to assist them in every way possible, so that they may, in the greatest possible comfort, worship the God of our fathers and our ancestors. And if they need a Torah scroll, he should attend to that with the utmost respect.

Of course, Rabbi Melamed also had another point to make:

[The Rabbi of the Kotel] should direct the women who wish to read from the Torah on Rosh Hodesh to Ezrat Yisrael, and should attend to all their needs with respect. And if there is any cause for worry that other Jews will grab Ezrat Yisrael at a time when the Conservative and Reform Jews wish to worship, he [the Rabbi of the Kotel] should direct them [the Orthodox Jews] to other places at the Kotel, so that Jews of all sorts should feel that they are beloved children of God at the Kotel.

Melamed, then, is advocating a much more tolerant stance, but slipped in his insistence that Women of the Wall cease their trying to change the status quo at the “regular” section of the Kotel.

In that view, Rabbi Melamed is hardly alone. Motti Karpel, a very thoughtful, hard-core right-wing religious columnist, also wrote a column (in Makor Rishon) about the Kotel issue. Advocating “historical Judaism, not hysterical Judaism” (we’ll look at his full argument much more carefully in a subsequent posting), he, too, urged a much more tolerant approach to the Reform and Conservative Jews at the Kotel, but for a different reason. (Goes without saying that I’m quoting him, not endorsing his views.)

In both Europe and in America, where the Reform movement is mostly based, it no longer constitutes a threat to Orthodox Judaism. There, Reform Judaism allows assimilating Jews the option of holding on to some connection to the Jewish people. In our days, when even identification with Zionism and the Jewish State is being lost among American Jews, this is the last pipeline to Jewish life that is left there. In that respect, Reform Judaism there, despite all its errors, plays a critical role.

In light of all these developments, it is perhaps time to show a more open approach to these movements ….

It’s time for historical Judaism to take care not to become hysterical Judaism. In Israel, these movements will forever remain peripheral, and they thus pose no threat. We must continue to express our fundamental disagreement with them over principles, but it may well be time to change our attitude to them. There is no point in sanctifying the battle.

Have we slipped into an era of extended olive branches?

Later today, Israel’s Supreme Court will resume hearings on what is commonly called “the Sheikh Jarakh eviction” issue. How the Court will rule, of course, remains to be seen. (We posted a podcast with Yotam Ben-Hillel, a leading attorney who represents Palestinian residential claims, in which he explained the complex legal issues at play here.)

One dimension of the long-simmering battle over these houses that seldom gets mentioned in the press is that the Arab occupants of the houses were offered a compromise, in which title to the homes would be declared to belong to the Jews, but the Palestinian residents of the buildings would be entitled to live there for the rest of their lives; in other words, there would be no evictions.

Palestinians rejected the compromise; they wanted to push the principle of what they consider justice. Agree with them or not, we can certainly understand them. Yet what they risk, of course, is eviction if the court rules in favor of the Jews who claim that the legal ownership is theirs.

Ironically, that situation isn’t all that different from what Rabbi Melamed is offering the Reform and Conservative movements. Perhaps more strongly than any leading Orthodox authority in Israeli history, he has spoken about them with respect and understanding. But he also wants the “women at the wall” protests, which take place in the “regular” section of the Kotel to cease. Will leaders of that movement take the implicitly offered deal?

Naftali Bennett and Yair Lapid have made it clear that they want to use their time in office to heal relations between Israel and Europe, between Israel and the White House, and between Israel and American Jews. On the first two, there’s already been some notable progress. On the latter, one can only hope that they will also be successful.

It takes two to tango, though, both in Sheikh Jarakh and at the Kotel. Even in this tinderbox region, olive branches are being extended. It remains to be seen who will reach out and accept.

I’ve been fascinated by the relationship between American Jews and Israel for a long time. A couple of years ago, I wrote this book on the subject:

I discuss some of the book’s claims in this podcast with Jonathan Silver of Mosaic Magazine.