Andy Bachman

For generations, the classical interpretation of this text is rooted in the idea that there are two Jerusalems, one on Earth and one in Heaven. Bound together, by fate, faith, destiny and history, one waits patiently for the other to be rebuilt.

This is the Jewish eschatological world-view. With the holy city having been destroyed by the Roman Empire in 70 AD, God was exiled along with the Jewish people. Through the agency of time and repentance–because, after all, it was “because of our sins that we were exiled from the land”– along with the assiduous and devoted observance of the commandments, the Jewish people would earn their way back into God’s grace and merit the coming of the Messiah, who would herald God and Israel’s return to the City of Peace.

But after nearly two thousand years of waiting, some Jews lost patience with the idea of a religious resolution to an ongoing historical crisis. Zionism, one might say, was a “revolution against the rabbis.” It was an exhaustively conceived, theoretical case for neither praying nor waiting but kickstarting, as techno-centric millenials might say, a diplomatic and pioneering effort of previously unimaginable proportions, to pick oneself up and go home. Not to wait for redemption but to redeem the land; not to pray one’s service but to labor in the practice of creating a social, economic and political infrastructure that would, within a half-century, build up and knit together centuries of Jewish hope with a radically sudden, immediate, irrevocable reality.

The older I get the more I appreciate this undeniable achievement. One hundred years ago, in 1915, the Ottoman Empire still ruled Palestine, not yet having lost the territory to the British, who would go on to win the war and inherit, with considerable and understandable reluctance, the responsibility for determining who could live in the land. By the 1920s it would be clear to all that Jews and Arabs would fight with every breath and fiber of their being for advantage and behave, in turn, in decidedly unheavenly ways to achieve their ends.

Prior to the Second World War and up to our own day, it was always the case that the majority of world Jewry would elect to live more closely to the Heavenly Jerusalem, leaving for dreamers, pioneers and persecuted refugees fleeing pogroms, rampant anti-Semitism, and ultimately, the Holocaust, Earthly Jerusalem. By war’s end and the balance of Diaspora power shifting to the United States, American Jews expressed their Zionism primarily through financial support and diplomacy. Like Gad, Reuben and the half-tribe of Menashe that asked Moses for permission to live outside the land and enjoy its economic wealth–while promising to offer support in time of war–American Jews are, for the most part, Zionists of the heart and the wallet.

We have opinions but we don’t really live them down there, on the ground. We remain lofty and distant, even heavenly in our ideals and aspirations for the Jewish homeland.

Our generosity is admirable. Even inspiring. And when it is rooted in the pluralistic and democratic values that we cherish so deeply as American Jews, we are even proud of the ways in which our influence shapes a more civil, diverse and expressive Israeli democracy.

We fought to free Soviet Jews, creating an aliyah of more than a million Russian Jews to Israel; in the hundreds of millions of dollars we philanthropically support a social service infrastructure that engages all of Israel’s citizens–Jewish and Arab; through the ballot we vote for candidates to public office based on their records of support for or against Israel. We have business relations; arts and cultural exchanges; Israelis working in our summer camps and Hebrew schools. We gain especially warm feelings from the Israelis who cut our hair, fix our cars, sell us soap, and serve us hummus right here at home that tastes just like the hummus in Tel Aviv. Even Birthright, a program that has taken nearly a half million Jews to Israel on a free ten-day trip since its inception a bit more than a decade ago, is not a mass aliyah movement. It’s meant to be–and finds its greatest success–in being a Jewish educational shot in the arm. Frankly, I love it.

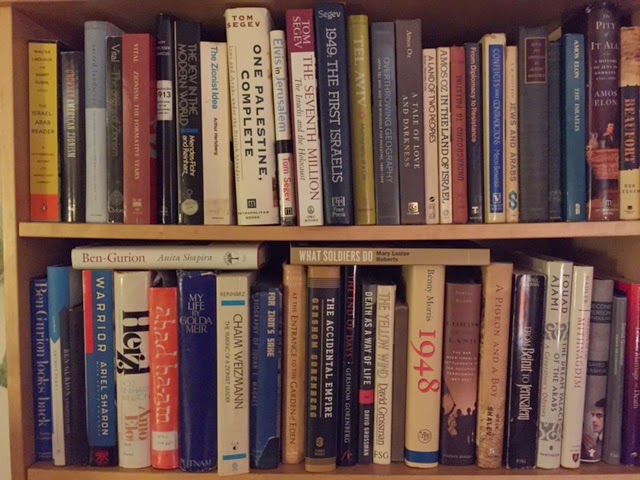

What we don’t do, with the exception of a relatively small measure of Orthodox Jews who vote with their feet by becoming Israeli citizens, is become Israeli ourselves. In the nearly120 years since the First Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland, we prefer our Zionism to remain here and not there. We lead with our mouths, even our hearts, but not our feet. The books on our shelves, the magnets on our refrigerators, the chocolates we eat at Hanukah time, enlighten and sweeten the distance between here and there. The blogs and letters to the editor we compose; the votes we cast for Gentiles who serve us in the hallowed halls of power; the t-shirts and slogans and stickers and demonstrations on campuses and town squares betray a darker, more shameful reality: We know what’s best; but far be it from us to live it.

This is the lens through which I view last week’s election in Israel. I was neither surprised by Bibi’s cravenly racist campaign rhetoric (there’s more than enough of that in American history) nor the trenchant partisan uses and abuses of Israel as a campaign cudgel between Republicans and Democrats gearing up for the 2016 presidential campaign.

But put it raw political terms. If Likud won the election in a landslide of 200,000 votes, triggering yet again a crisis for a certain segment of the liberal American Jewish elite (of which, I guess, I’m a reluctant member) imagine a different scenario of 10,000 liberal American Jews making aliyah each year, for twenty years, and causing, in turn, their own revolution inside Israeli electoral life.

Impossible? A pipe dream? Why?

Since the early Reagan era in the United States the Republican strategy has been to win state houses across the country, redraw districts, and ensure power and influence for generations. The long game, well-organized and executed with precision, wins. An opportunist like Scott Walker is able be part of a political movement to dismantle the New Deal and the Great Society because he stands on the shoulders of more than three decades of a strategy to put him in place to do it.

Does liberal Zionism have the strength, resolve and patience to deploy a similar strategy?

I read about last week’s election in Israel and when I look up from the screen, I go look in the mirror. The resolution to challenges in Israel begin with me. And you.

Who are we as Jews? And what are we really willing to do about it?

Andy Bachman has a blog called Water Over Rocks

Re-posted with permission

Andy Bachman