Jonathan Sacks z”l covenant and conversations: Not All as it Seems

Excerpt from the book of Leviticus weekly reading: from Shemini

We err if we think of God as capricious, jealous, angry: a myth spread by early Christianity in an attempt to define itself as the religion of love, superseding the cruel/harsh/retributive God of the “Old Testament.” When the Torah itself uses such language it “speaks in the language of humanity” (Berakhot31a) – that is to say, in terms people will understand.

In truth, Tanakh is a love story through and through – the passionate love of the creator for His creatures that survives all the disappointments and betrayals of human history. God needs us to encounter Him, not because He needs mankind but because we need Him. If civilization is to be guided by love, justice and respect for the integrity of creation, there must be moments in which we leave the “I” behind and encounter the fullness of being in all its glory.

That is the function of the holy – the point at which “I am” is silent in the overwhelming presence of “There is.” That is what Nadav and Avihu forgot – that to enter holy space or time requires ontological humility, the total renunciation of human initiative and desire.

The significance of this fact cannot be over-estimated. When we confuse God’s will, we turn the holy – the source of life – into something unholy and a source of death. The classic example of this is “holy war,” jihad, Crusade – investing imperialism (the desire to rule over other people) with the cloak of sanctity as if conquest and forced conversion were God’s will.

The story of Nadav and Avihu reminds us yet again of the warning first spelled out in the days of Cain and Abel. The first act of worship led to the first murder. Like nuclear fission, worship generates power, which can be benign but can also be profoundly dangerous.

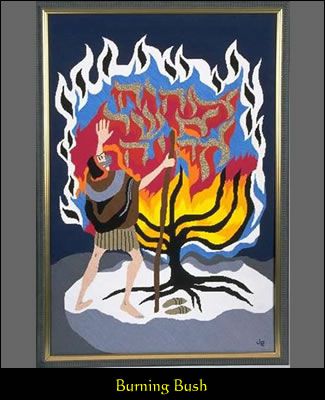

The episode of Nadav and Avihu is written in three kinds of fire.

First there is the fire from heaven:

Fire came forth from before God and consumed the burnt offering. (Lev.9:24

This was the fire of favour, consummating the service of the Sanctuary.

Then came the “unauthorized fire “offered by the two sons.

Aaron’s sons Nadav and Avihu took their censers, put fire in them, and added incense; and they offered unauthorised fire before the Lord, which He had not instructed them (to offer). (Lev. 10:1)

Then there was the counter-fire from heaven:

Fire came forth from before the Lord, and it consumed them so that they died before the Lord. (Lev. 10:2)

The message is simple and intensely serious: Religion is not what the European Enlightenment thought it would become: mute, marginal, and mild. It is fire – and like fire, it warms but it also burns. And we are the guardians of the flame. (pgs: 146-147)

In this exchange between two brothers, a momentous courage is born: the courage of an Aaron who has the strength to grieve and not accept any easy consolation, and the courage of a Moses who has the strength to keep going in spite of grief. It is almost as if we are present at the birth of an emotional configuration that will characterise the Jewish people in centuries to come. Jews are a people who have had more than their share of suffering. Like Aaron, they did not lose their humanity. They did not allow their sense of grief to be dulled, dead-ened, desensitised. But neither did they lose their capacity to continue, to carry on, to hope. Like Moses, they never lost faith in God. But like Aaron, they never allowed that faith to anaesthetise their feelings, their human vulnerability.

That, it seems to me, is what happened to the Jewish people after the Holocaust. There were, and are, no words to silence the grief or end the tears. We may say – as Moses said to Aaron – that the victims were innocent, holy, that they died al kiddush Hashem, “in sanctification of God’s name.” Surely that is true. Yet nonetheless, “Aaron remained silent.” When all the explanations and consolations have been given, grief remains, unassuaged. We would not be human were it otherwise. That, surely, is the message of the book of Job. Job’s comforters were pious in their intentions, but God preferred Job’s grief to their vindication of tragedy.

Yet, like Moses, the Jewish People found the strength to continue, to reaffirm hope in the face of despair, life in the presence of death. A mere three years after coming eye to eye with the Angel of Death, the Jewish people, by establishing the State of Israel, made the single most powerful affirmation in two thousand years that Am Yisrael Chai, the Jewish people lives.

Moses and Aaron were like two hemispheres of the Jewish brain: human emotion on the one hand, faith in God, the covenant, and the future on the other. Without the second, we would have lost our hope. Without the first, we would have lost our humanity. It is not east to keep that balance, that tension. Yet it is essential. Faith does not render us invulnerable to tragedy but it gives us the strength to mourn and then, despite everything, to carry on. (pgs. 154-155)