Victor Rosenthal – Israel: The Narrative and the Objective

Argumentum ad consequentiam – Concluding that an idea or proposition is true or false because the consequences of it being true or false are desirable or undesirable.

Micah Goodman believes that there is, at least today, no solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. But he has a plan:

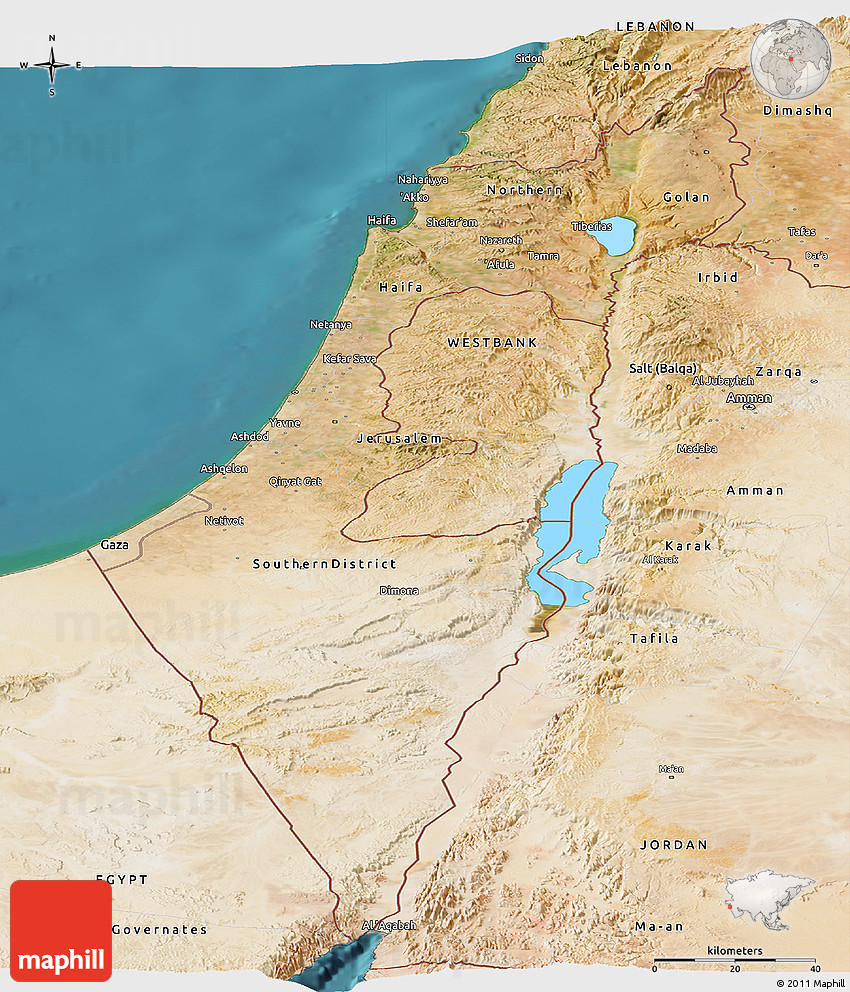

The concept of shrinking the conflict means pursuing any policy that significantly boosts Palestinian self-government without jeopardizing Israeli security. At the heart of shrinking the conflict is an effort to create territorial contiguity between Palestinian autonomous islands in the West Bank, connect this Palestinian autonomy to the wider world, and promote Palestinian economic prosperity and independence. The purpose of this strategy is to transform the West Bank’s fragmented and fragile network of autonomous islands into a contiguous and prosperous polity. Shrinking the conflict would give the Palestinians what they currently lack: a critical mass of self-governance.

Importantly, this would not be in the context of a peace treaty and the Palestinians would not be expected to forgo their claims for a “right of return” or to recognize Israel. This is about shrinking the conflict, not ending it. …

Shrinking the conflict wouldn’t bury the dream of a full peace accord. It would do exactly the opposite. After the Palestinians’ self-governing autonomy is stabilized, it might eventually be upgraded into a fully independent state in the context of a peace treaty. But this would not be the only option. It might also become part of a confederation with Israel, or the option of political union with Jordan might return to the table.

So what is the problem here? There are two. One is that he does not listen to Palestinians, or he doesn’t take what he hears from them seriously. Like us, the Palestinians have a story, a historical Narrative that explains who they are and how they are a people. Like us, they teach it in their schools, and it informs their literature, art, their religion and their politics. When they say “I am a Palestinian,” they are referring to this Narrative and their place in it.

And also like us, along with the Narrative, there comes a collective Objective that is supported by it. Part of being a Palestinian, along with finding one’s place in the narrative, is yearning for the achievement of the Objective.

The Palestinian Narrative tells that they are a people that developed over hundreds or thousands of years in the land that we call Eretz Yisrael and they call Filastin, and that the Jews violently stole it from them, expelled them, took away their land, possessions, and honor: the Nakba. According to this story, the land and everything in it belongs to them. We are not even related to the biblical Jews or even a people; we are a motley group of Europeans or Khazars, or whatever.

Everything about this story, including what it says about who they are and who we are, is wrong. But although most Palestinians are Muslims, they are also Palestinists, to whom this narrative is holy. It doesn’t matter if a Palestinian is a barely literate shepherd or a university professor, doctor, or engineer. It is irrelevant if the Palestinian is Muslim, Christian, or an atheist. It doesn’t matter if he lives in Ramallah, Umm al-Fahm, or Tel Aviv. The Narrative is holy and it represents a higher truth than anything found in Western history books, archaeology, or genetics. Criticizing the narrative to a Palestinian is like telling a religious Christian or observant Jew that science has determined that the humans are descended from apes. It doesn’t contradict his belief; at most, it exists alongside it in a realm of lower truth.

The Narrative supports and justifies the Objective, and fuels the Palestinian passion to attain it. The objective, of course, is the elimination of the Jewish presence in all of Filastin, and the return of their land, possessions, and honor to the Palestinian people from whom it was stolen.

Understanding this makes it possible to understand otherwise inexplicable aspects of their behavior. Why did they reject the Covid vaccines that Israel has now sent to South Korea, which is pleased to receive them? Why, over and over, do they resist initiatives designed to be mutually beneficial to Israelis and Palestinians? Why is “normalization” a dirty word? Why did both Arafat and Abbas find it impossible to accept a sovereign state in the territories on the condition that they would recognize that Israel is the state of the Jewish people? Why did they loot and burn the greenhouses in Gaza?

It is undeniable that Palestinians, like anybody else, want economic prosperity and independence. But no Palestinian will agree to give up his dream for those things. You might as well set up a Golden Calf in Mea Shearim and try to pay the residents to bow down to it.

We gave the Palestinians the territorial contiguity that they wanted in Gaza, but it didn’t “shrink” the conflict. It just made it easier to move rocket launchers around, in pursuit of the Objective. And similar actions will not reduce conflict in Judea and Samaria. The Palestinians pocket concessions that are consistent with their Objective, and reject those that weaken it. They will not give it up. And therefore, the “shrinking” program will not reduce conflict, it will only strengthen the enemy.

I said there were two problems with Micah Goodman’s program. The other one is not exactly a defect in it, but a psychological explanation of how it came into being. And that is that Goodman has fallen into the trap of argumentum ad consequentiam. He believes, as do many on the Left and Center, that there is no alternative to Jewish-Arab coexistence. The thought that it might be impossible leaves him at sea. In his book, “Catch-67: The Left, the Right, and the Legacy of the Six-Day War,” Goodman explains very persuasively why abandoning Judea and Samaria would be disastrous to Israel’s security, while at the same time, taking control of and responsibility for its hostile population is also untenable.

Faced with this dilemma, he argues for bypassing the problem, choosing not to try to solve it, but rather to ameliorate it as much as possible, in the hopes that someday the desire for “peace and prosperity” will cause the Palestinians to forget their Narrative and abandon their Objective.

But that won’t happen either. The Palestinians will not let go of their Objective and they will not forget why. Implementing Goodman’s program will only give them more leverage.

And now we come to the ad consequentiam part. Goodman is no dummy. He must understand that there is only one option open to the Jewish people if they are to obtain their own Objective, which is to live in peace in Eretz Yisrael. And that is to persuade or encourage the Palestinians to leave (here are some ideas) – or, failing that, to expel them by any means necessary.

This existential situation – that we cannot coexist with them, that they are an implacable enemy, and that either they go or we do – is too painful for many to bear. It is cognitively dissonant, and it places our humanitarian values in direct conflict with our drive to preserve ourselves as a people. So we do not admit that it is true.

But the real world doesn’t work that way. What’s true is true. And the quickest way to become extinct, either as an individual or as a people, is to ignore reality.